Jackson Hole: From Volcker Taming Inflation in 1982 to Powell Navigating Risks in 2025

03:17 August 25, 2025 EDT

Key Points:

1. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled a potential shift toward accommodative monetary policy in his speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, heightening market expectations for a rate cut in September.

2. In 1982, then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker used the Jackson Hole forum to advance policies aimed at curbing persistent high inflation, laying the groundwork for a historic bull market.

3. The legacy of the Jackson Hole symposium underscores a central principle: the effectiveness of central bank policy depends not only on implementation but also on how well markets understand and anticipate policy intentions.

Jackson Hole, Wyoming, originally a vacation town known for its cowboy culture, has gained international prominence since 1982 as the host of the annual global central banking conference. It has become a key venue for observing the direction of monetary policy worldwide.

In 1982, then-Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker advanced policies at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium to tackle prolonged high inflation, creating conditions for subsequent U.S. economic stability and long-term capital market growth. In August 2025, Fed Chair Jerome Powell indicated a potential adjustment in monetary policy at the same conference, responding to a weakening labor market and tariff-induced price increases for certain goods. His dovish signals have strengthened market expectations for a rate cut in September.

The 1982 Meeting: Policy Shift Catalyzes a Bull Market

The 1982 Jackson Hole symposium marked a significant transformation in the Federal Reserve's monetary policy framework and laid the foundation for the U.S. economy to escape the mire of stagflation and embark on a path of long-term growth.

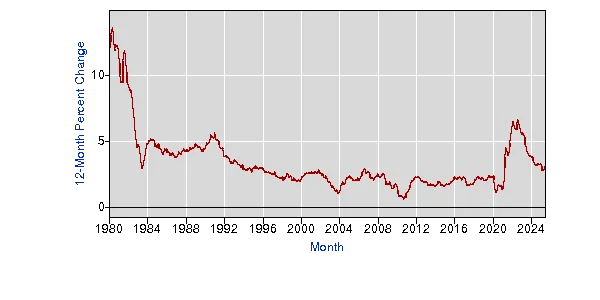

The economic environment at that time exhibited the classic characteristics of stagflation, with simultaneously high inflation and high unemployment—the inflation rate peaked at 14.8% in 1980, while the unemployment rate rose to a peak of 10.8% by November 1982. Between April 1979 and December 1982, the U.S. industrial production index showed a “W-shaped” pattern of decline, recovery, and renewed decline, reflecting persistently weak overall performance. Then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker implemented an aggressive tightening policy from 1979 to 1982, pushing the federal funds rate to around 20%. This strategy of “trading recession for inflation control,” though intensifying short-term economic pain, successfully brought inflation down to 4.6% by the end of 1982.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

The core significance of the 1982 Jackson Hole meeting lay in its clear signaling of policy intentions and the transition in operational framework. With the theme “Monetary Policy Issues in the 1980s,” the symposium shifted its focus from agricultural policy to monetary policy for the first time, establishing its role as a global platform for central bank policy dialogue. Volcker used the forum to communicate a clear policy priority: first stabilize prices, then restore growth. This stance set the tone for subsequent monetary policy adjustments—between July and the end of 1982, the Federal Reserve lowered the discount window rate seven times. Over the same period, the 90-day Treasury bill rate declined significantly, and bank prime rates also gradually decreased.

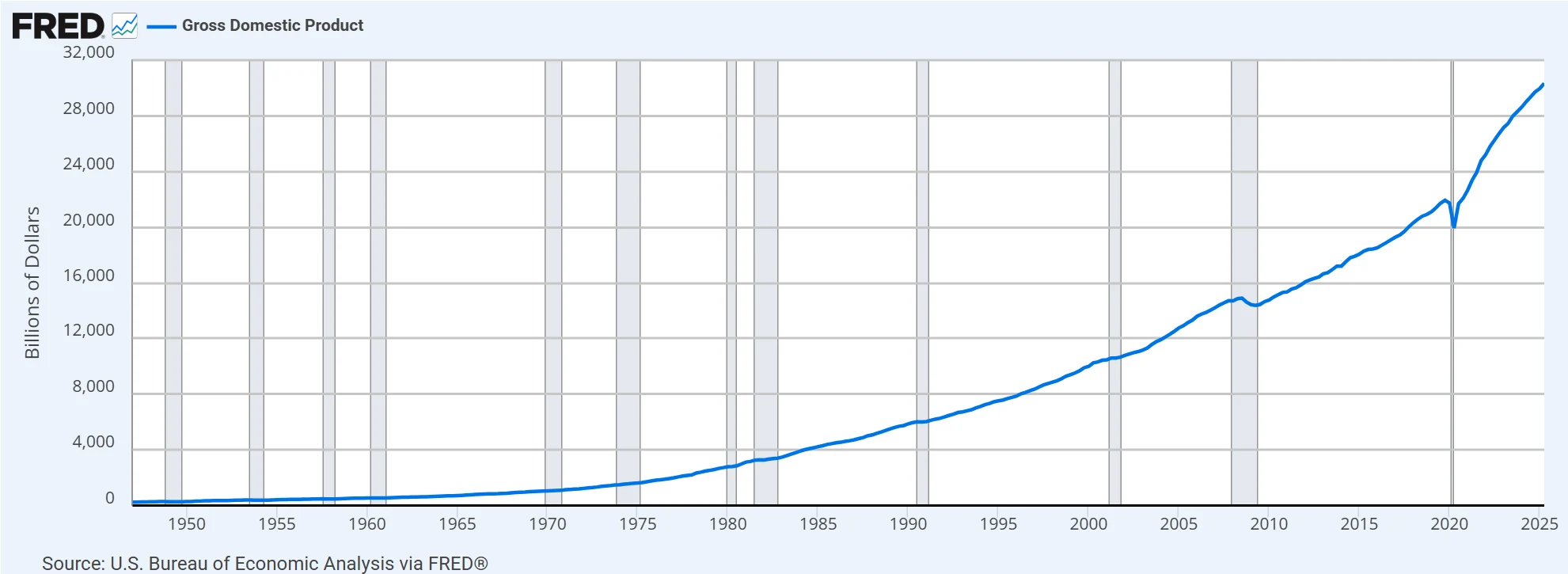

Source: FRED

This systematic easing helped alleviate the liquidity crisis triggered by the collapse of Penn Square Bank and mitigated market concerns about deflation.

The market impact of this policy shift was particularly evident in 1982. In August of that year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average stabilized around the 777 level and began a rapid rebound, rising approximately 30% within two months and initiating a sustained super bull market. From August 1982 to the end of 1983, the Dow Jones Industrial Average increased by over 60%.

Source: TradingView

The launch of this bull market was built on multiple positive signals: controlled inflation reinforced expectations of monetary stability (with inflation falling to 3.2% in the first half of 1983), economic recovery data—4.5% GDP growth in 1983 and 7.2% in 1984—validated policy effectiveness, and the Federal Reserve’s operations and enhanced communication helped stabilize market expectations.

Source: FRED

The success of the 1982 policy turnaround also benefited from lessons learned from historical experience. Unlike the Federal Reserve’s tightening policies during the Great Depression of the 1930s, Volcker shifted to easing promptly after inflation was brought under control, stabilizing the financial system through liquidity injection. This approach, combined with open trade policies rather than protectionism, prevented the economy from sinking into a deeper recession.

The 2025 Meeting: The Economic Dilemma and the Logic Behind the Policy Pivot

The 2025 Jackson Hole symposium confronted an economic environment distinctly different from yet equally complex as that of 1982. In his August 22 speech, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell sent a clear dovish signal, shifting policy focus toward downside risks in the labor market. This change marks another significant adjustment in the Federal Reserve's monetary policy framework.

The updated Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, released during the symposium, formally announced a return to a "Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT)" framework, moving away from "Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT)." The removal of the phrase "to compensate for employment shortfalls" indicates a policy approach now more oriented toward "preemptive prevention" rather than "post-hoc remediation," reflecting the Fed's evolving assessment of current economic risks and its policy philosophy.

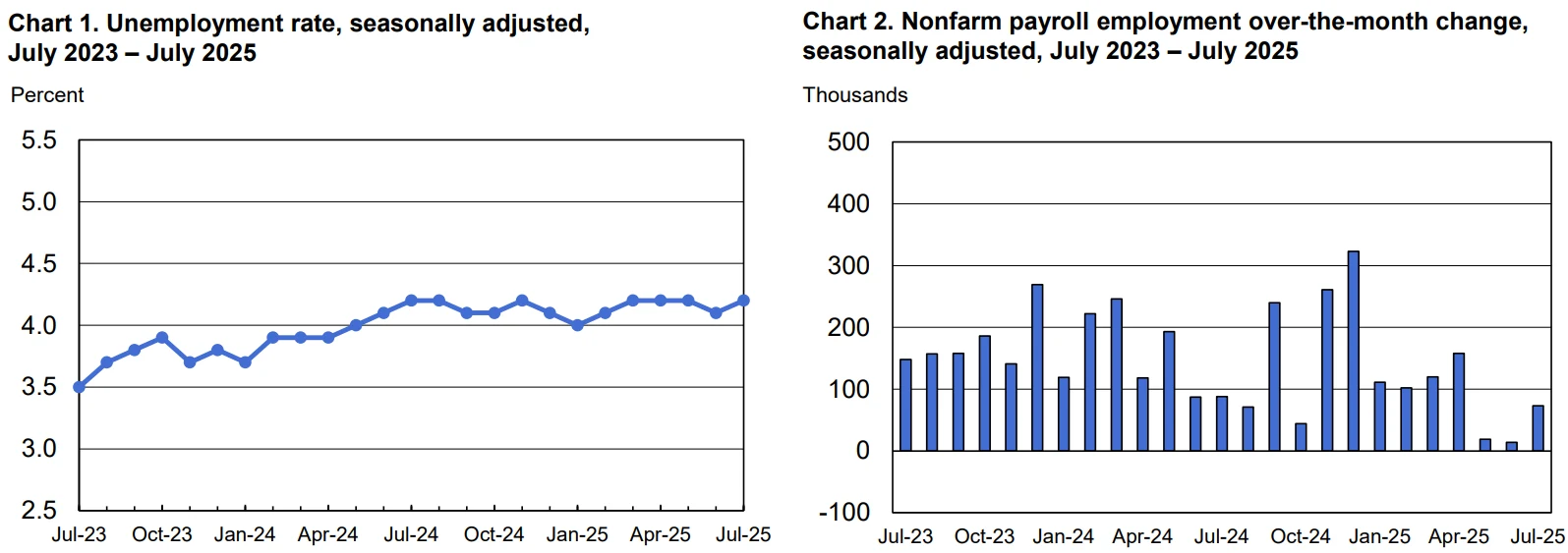

The current U.S. economy presents a combination of "labor market weakness and persistent inflation." Employment data for July 2025 showed only 73,000 new nonfarm payroll jobs, significantly below market expectations of 110,000. Furthermore, data for May and June were substantially revised downward by a total of 258,000 jobs, pulling the three-month average job growth down to a low of 35,000. Although the unemployment rate only edged up to 4.2%, Powell pointed out that this surface-level stability stems from a simultaneous slowdown in both labor supply and demand—an "unusual balance" that harbors the risk of a surge in layoffs and a rapid rise in unemployment.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

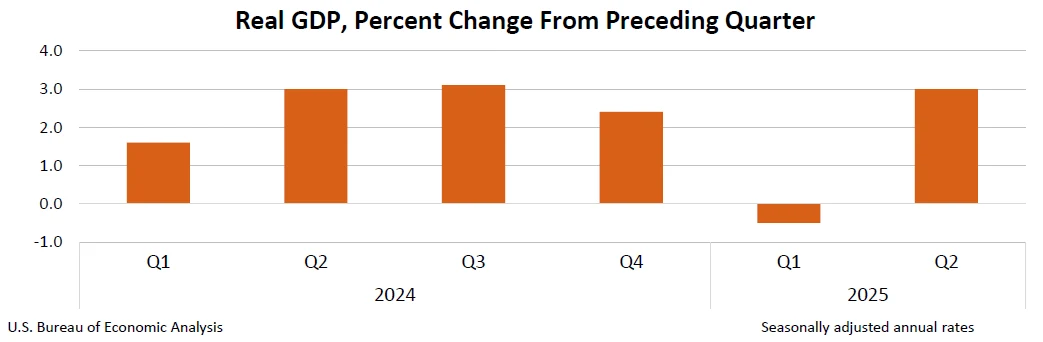

Economic growth momentum has also weakened. The U.S. real GDP growth rate (annualized) for the second quarter of 2025 was 3%.

Source: BEA

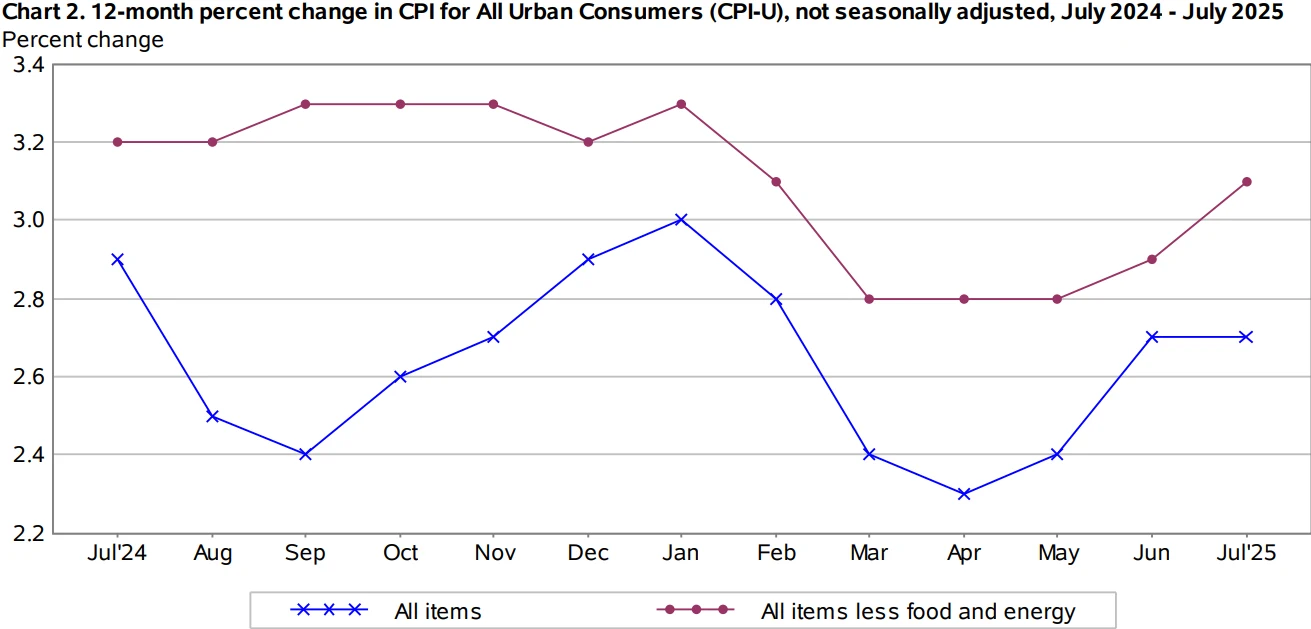

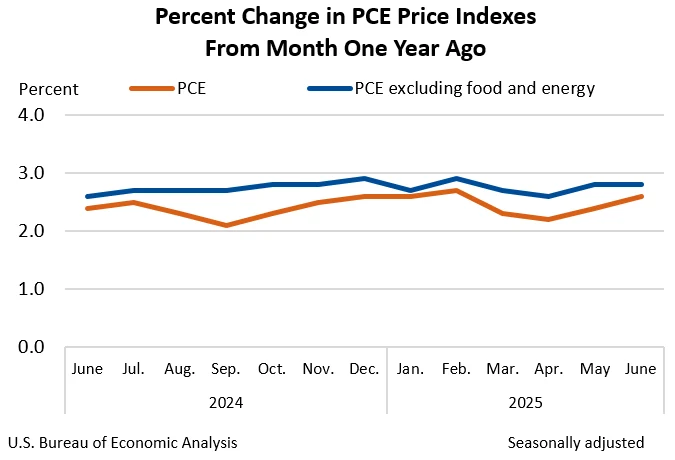

Inflationary pressures, meanwhile, exhibit policy-driven characteristics. In July 2025, core CPI rose 3.1% year-over-year, while the core PCE price index recorded 2.7% in May. Both indicators show a slight upward trend and remain above the Fed's long-term target of 2%. Of particular note, new tariff policies enacted by the Trump administration, effective August 7, 2025, pose additional upside risks to inflation.

Source: BEA

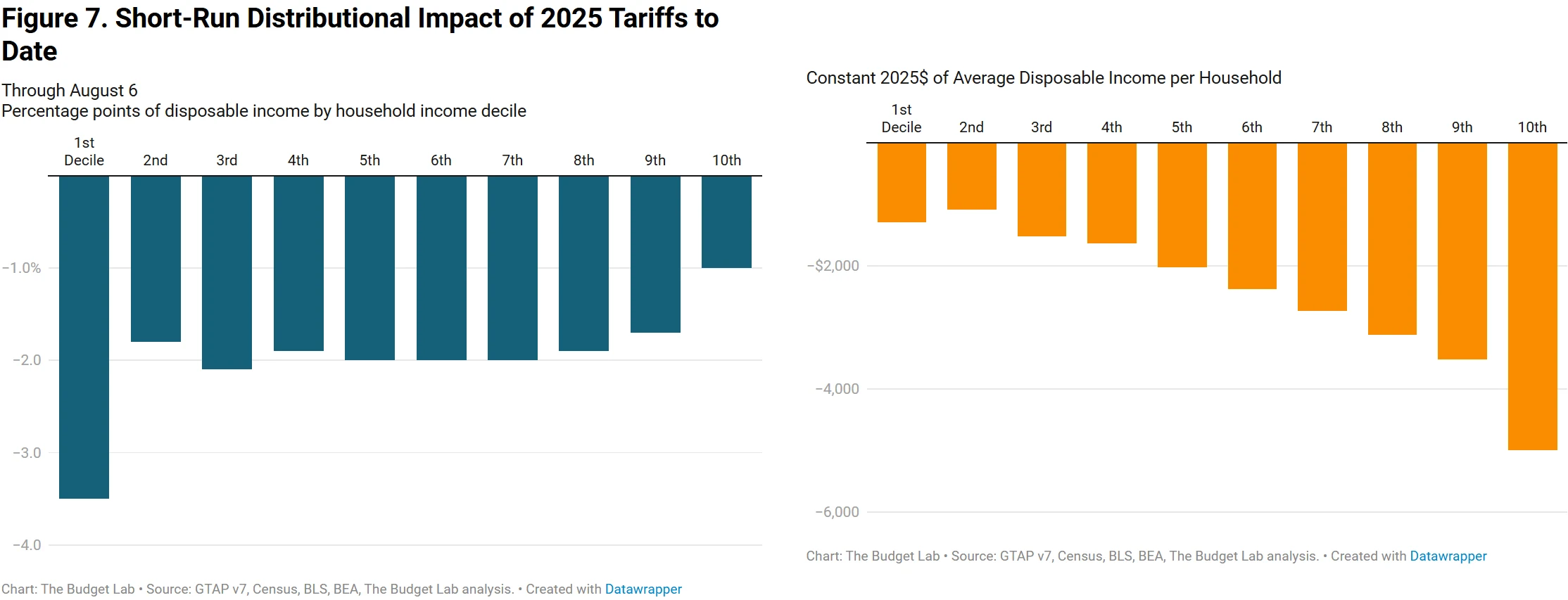

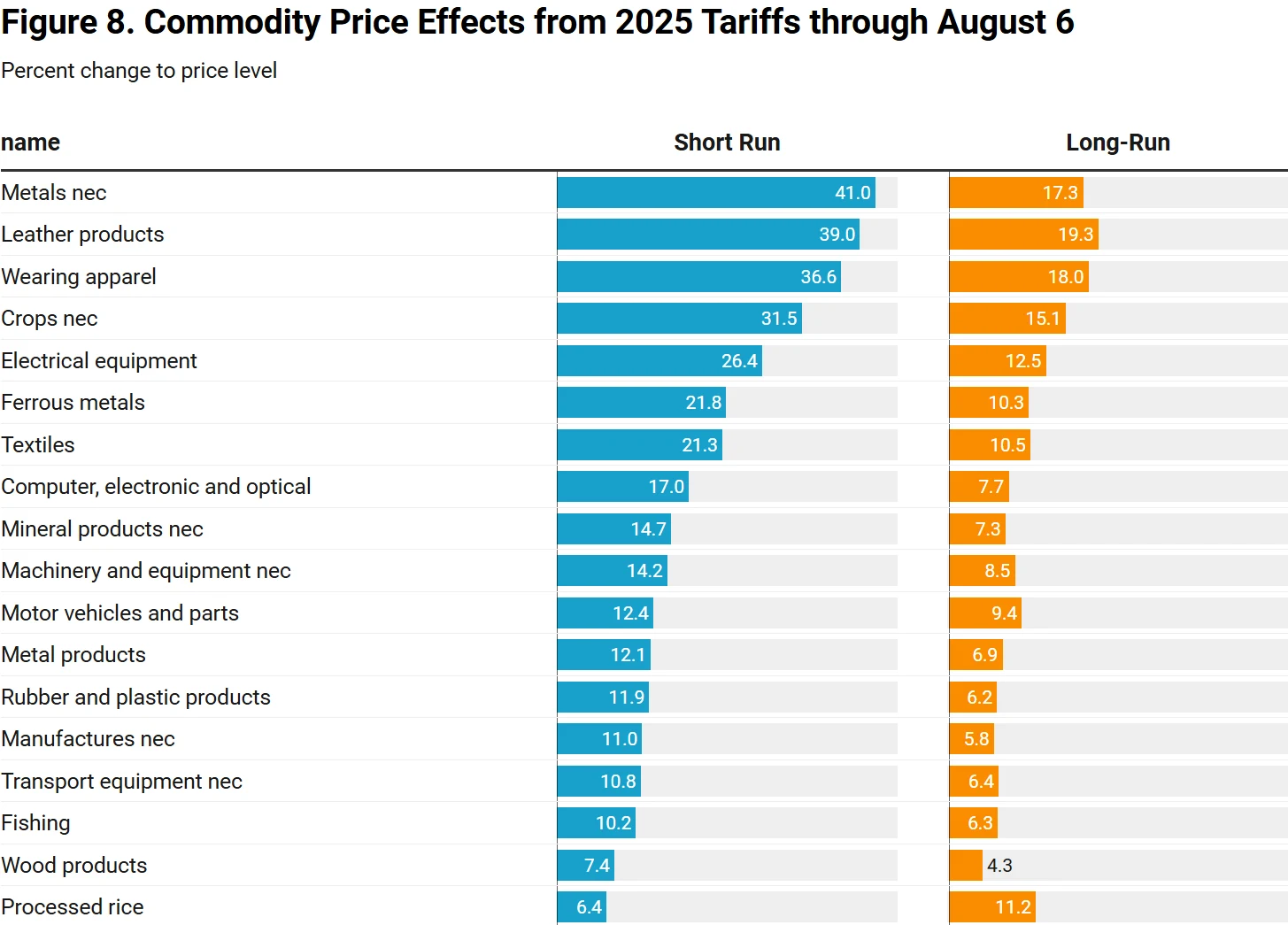

Estimates from the Yale Budget Lab indicate that these tariffs will increase the average American household's annual expenses by $2,200, raising goods prices by 1.7%-1.8% in the short term. A key aspect of Powell's assessment at the symposium was characterizing the tariff effects as a "one-time price level shock" rather than a source of persistent inflationary pressure, providing a theoretical basis for the policy shift.

Source: The Budget Lab at Yale

The adjustments to the monetary policy framework reflect the Fed's reassessment of balancing its dual mandate. The 2025 revisions include three key changes: first, removing the description of the "Effective Lower Bound (ELB) as a core economic feature," hinting at a reevaluation of the Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) era; second, abandoning the "inflation overshooting" strategy, indicating a move away from compensatory easing after inflation persisted above target; third, reinterpreting the "maximum employment" goal to focus more on "employment shortfalls" rather than "an overheated labor market." These adjustments grant the Fed greater policy flexibility when confronting employment downside risks.

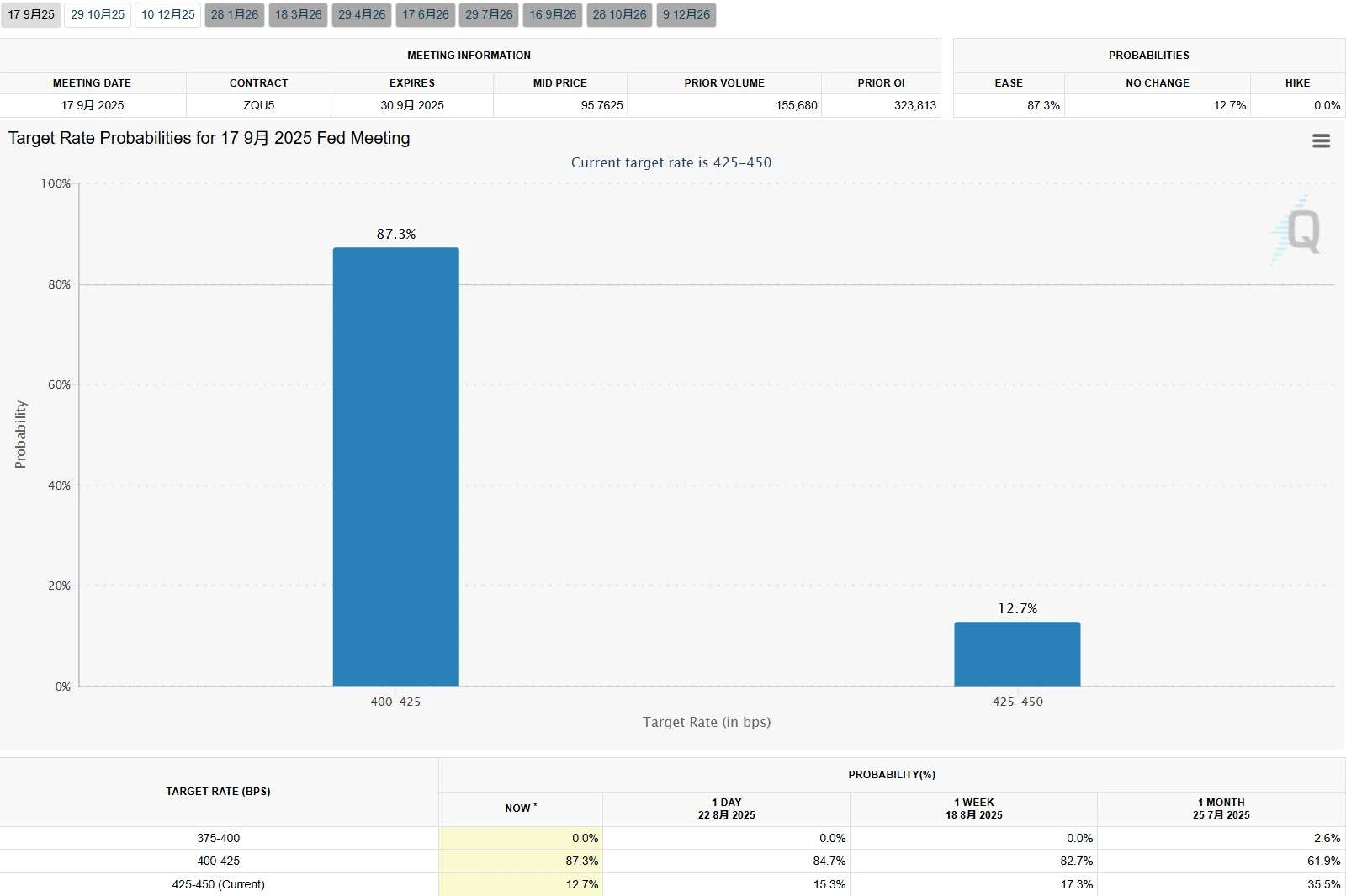

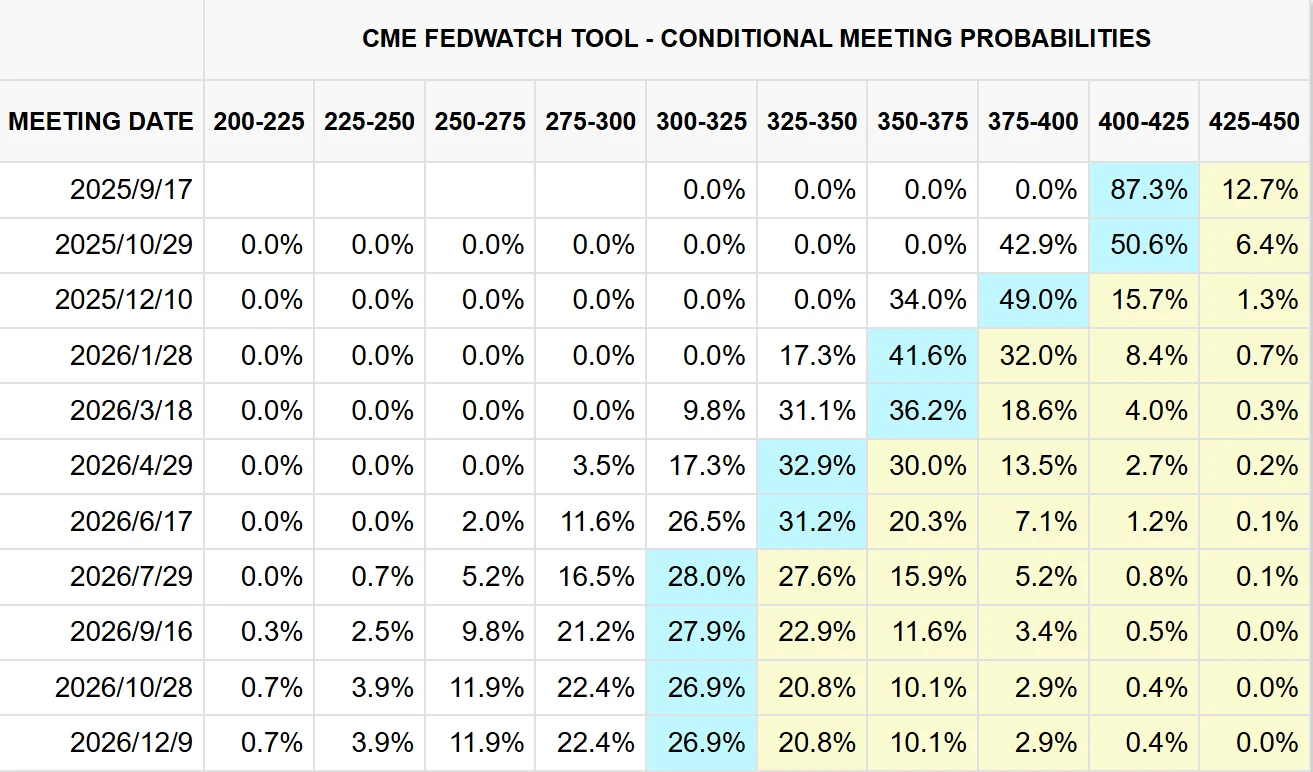

The market reaction to Powell's speech was swift. Data from the CME Group showed that the market-implied probability of a 25-basis-point rate cut in September surged to nearly 90% following his remarks.

Source: CME

Financial markets exhibited a classic reaction pattern to easing expectations: the S&P 500 recorded its largest gain since May, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at a record high.

Source: TradingView

The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note fell more than 7.5 basis points to 4.256%, the U.S. Dollar Index declined 0.8%, while gold, copper prices, and the cryptocurrency Ethereum all moved higher.

Source: TradingView

However, while markets widely interpreted Powell's speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium as a clear signal for a September rate cut, Jonathan Levin, a Stanford economics professor and former director of an economic policy research center, cautioned in a Bloomberg column that the market's dovish interpretation might be excessive. He argued that the core message of Powell's speech was not unconditional easing; a deeper reading reveals he was grappling with the difficult balance between labor market weakness and high inflation risks. Levin emphasized that if the Fed does cut rates, the reason would likely be that the economy is in trouble, forcing the central bank to intervene, rather than because inflation has cooled.

Policy Divisions and an Uncertain Rate-Cut Course

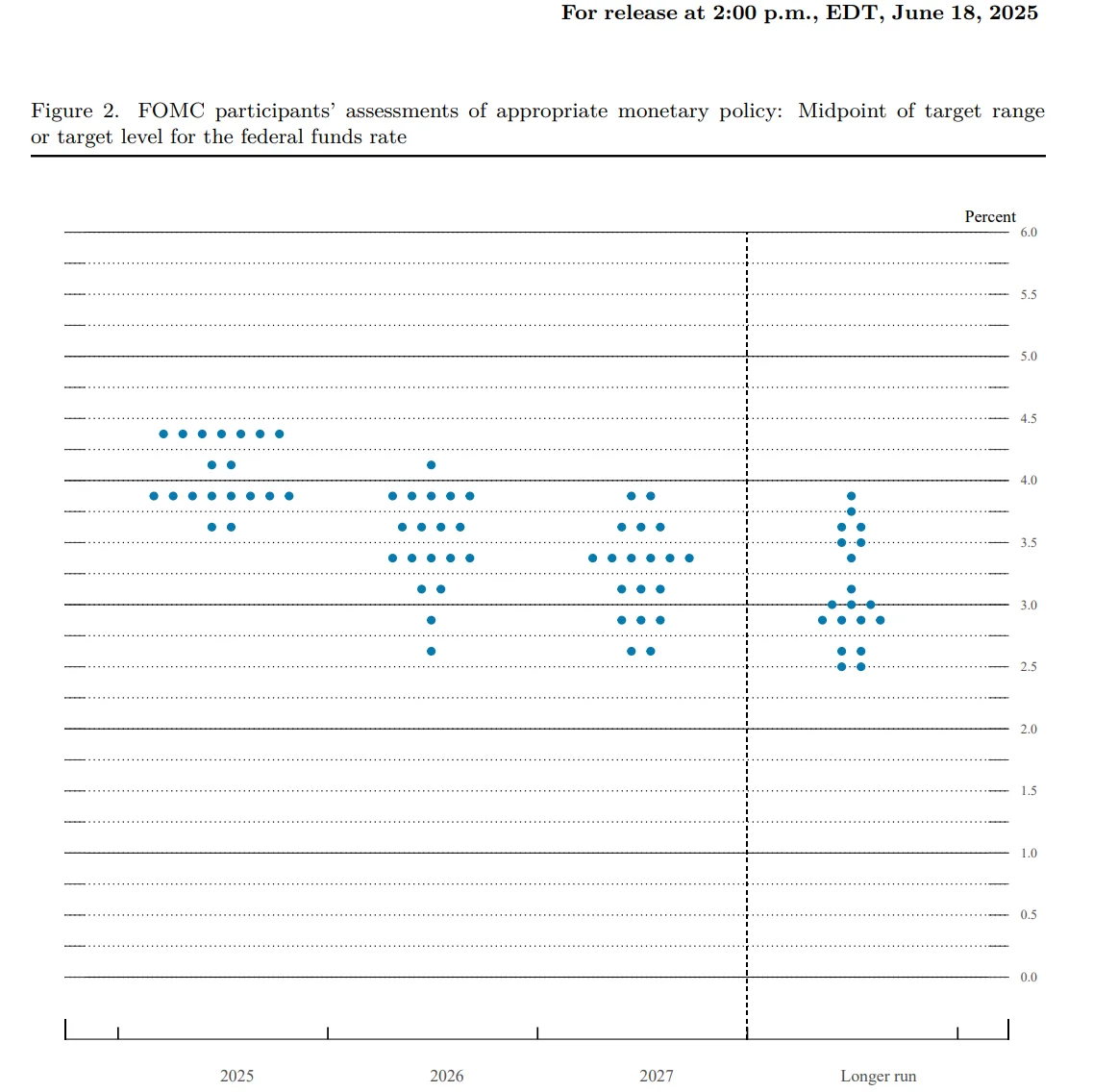

The divergence within the Federal Reserve over the path of rate cuts in 2025 has reached its most pronounced level in nearly 30 years. This split is reflected not only in voting outcomes but also in differing assessments of the economy and in how officials rank policy priorities.

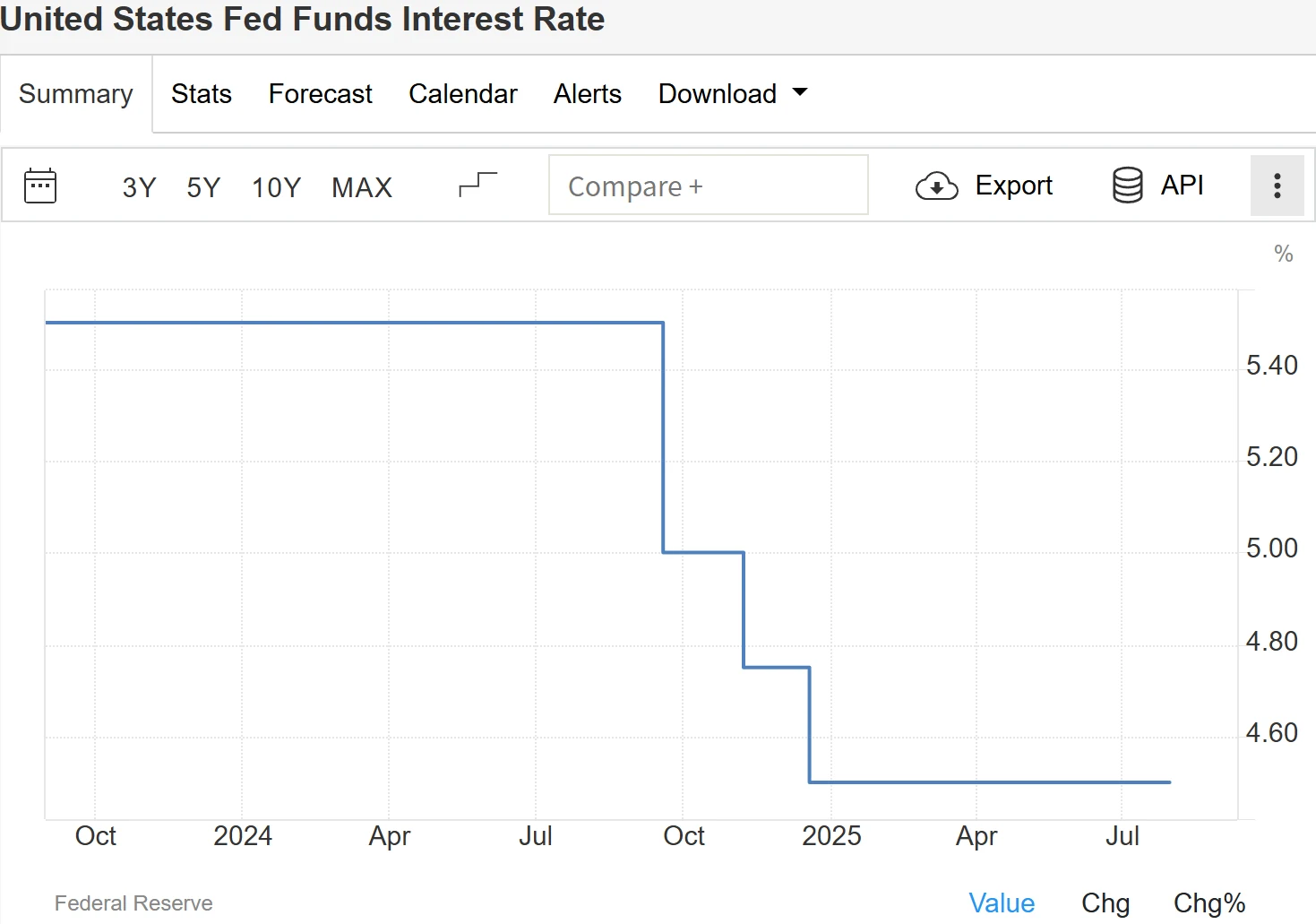

The July 2025 policy meeting saw, for the first time since 1992, two governors simultaneously dissent from the rate decision. Governors Michelle Bowman and Christopher Waller voted against maintaining the 4.25%–4.5% target range, advocating instead for an immediate 25-basis-point cut. The divide widened after the Jackson Hole conference, coalescing into three distinct camps.

Source: Federal Reserve

The dovish camp, represented by some regional Fed presidents and governors, stresses the risk of a rapid deterioration in the labor market and argues that delaying cuts could deepen a recession. They cite evidence including: average nonfarm payroll gains of only 35,000 over the past three months, well below the level needed to absorb natural labor-force growth; a 4% drop in durable goods orders pointing to weak domestic demand; and turbulence in emerging markets such as Mexico that could spill over into the U.S.

Doves argue for at least three cuts this year totaling 75 basis points to prevent the jobs market from sliding into a deeper contraction. Their logic echoes Paul Volcker’s 1982 easing, contending that decisive action is warranted when deflation risks first emerge.

The hawkish camp focuses on sticky inflation and the potential impact of tariff policy. Its standard-bearers include St. Louis Fed President Alberto Musalem and Cleveland Fed President Beth Hammack. They point out that core inflation remains 1.1 percentage points above target, and they question the Fed’s assumption that the tariff shock will be “one-off.” Research from Yale’s Budget Lab indicates that the new tariffs could concentrate upward pressure on new-car prices in 2026, and history shows that once inflation expectations become unanchored, restoring price stability exacts a higher economic cost. Hawks judge the current stance to be moderately restrictive and favor waiting for clearer evidence of disinflation, opposing any preemptive cuts.

Source: The Budget Lab at Yale

Centrists, led by Chair Jerome Powell, occupy the decision-making middle and prefer a “cut once, then watch” approach. This group acknowledges downside risks in the labor market but also worries that cutting too early could rekindle inflation, seeking balance between the Fed’s dual mandate. Powell emphasized at Jackson Hole that “monetary policy is not on a preset course,” and that future decisions will be based on “the totality of the evidence,” including the forthcoming August nonfarm payrolls and CPI reports.

This caution reflects the complexity of the current backdrop—unlike 1982, when inflation was clearly trending lower, the 2025 outlook is clouded by tariff policy, shifts in labor supply and demand, and other variables.

External political pressure adds another complication to the Fed’s decision-making.

Since early 2025, President Donald Trump has repeatedly called for steep rate cuts, criticizing high rates as harmful to growth and even threatening to fire Powell. While the Fed underscores its independence, the dissenting votes by two Trump-appointed governors in favor of cuts blur the line between politics and policy. This contrasts with the relative freedom from political interference during Volcker’s tenure in 1982 and has sparked concerns about erosion of central bank independence. Treasury Secretary Bessent’s suggestion that Powell should leave the Fed after his term ends in 2026 has further heightened uncertainty about policy continuity.

A data-dependent policy path is especially evident in 2025. Goldman Sachs and others note that the upcoming August jobs report will be pivotal for a potential September cut: payroll gains below 100,000 would confirm the need to ease. Inflation is equally crucial—economists expect July core PCE to tick up to 2.9% year over year. While that reading is unlikely to block a September move, it could shape the cadence of subsequent easing.

Markets currently assign a better-than-90% probability to a September cut, but only about a 55% chance of a second cut by year-end, reflecting a cautious view of the policy trajectory.

Source: CME

The Path Ahead

Based on signals from the 2025 Jackson Hole Symposium and current economic data, the Federal Reserve’s policy path is likely to exhibit a high degree of scenario dependence. Different combinations of economic variables could lead to sharply divergent policy outcomes.

The baseline scenario expects the Fed to begin cutting rates by 25 basis points in September, with the probability of this move rising to nearly 90% after Jackson Hole. The key trigger is labor market deterioration—three consecutive months of weak job growth with significant downward revisions to prior data—aligning with the Fed’s new policy philosophy of “preemptive action rather than post-crisis response.” Under this scenario, the Fed would lower the policy rate from the current 4.25%–4.5% range to 4.0%–4.25% and highlight in its statement that it is “closely monitoring downside risks to employment.”

Subsequent policy adjustments would be highly data-dependent. If August nonfarm payroll growth remains below 100,000 and core PCE holds steady at 2.8%–2.9%, a second cut in December is likely, bringing the total 2025 easing to 50 basis points.

Two main risk scenarios could alter this path. The first is unexpectedly sticky inflation, particularly from the lagged effects of tariffs. Yale’s Budget Lab warns that tariffs implemented in 2025 could fully feed through to consumer prices in 2026, exerting renewed upward pressure on inflation.

Source: BEA

If this materializes, the Fed may have to pause rate cuts—or even reconsider rate hikes in 2026—creating a “cut-pause-hike” sequence. The second risk is a sharper downturn in the labor market. If July’s 73,000 payroll gain falls further below 50,000, recession fears could force the Fed into more aggressive easing in Q4 2025, with annual rate cuts totaling 75–100 basis points.

Source: TradingEconomics

The transmission of monetary policy will vary across markets and sectors. Equities have already priced in easing expectations, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average hitting record highs after the meeting. However, valuations have partially discounted the impact of looser policy. Historically, when rate cuts began in 1982, the S&P 500 traded at about 8 times earnings; in August 2025, the multiple stands at 22, suggesting that higher valuations may limit further upside. In bonds, the 10-year Treasury yield may gradually fall toward the 3.8%–3.9% range as the easing cycle unfolds. In currency markets, the dollar’s downtrend will depend on policy moves by other major economies; if the ECB eases simultaneously, dollar depreciation may be contained.

Source: TradingView

From a historical perspective, 2025 differs markedly from 1982. The rate cuts of 1982 marked a systemic shift after inflation had been firmly controlled, with clear policy goals and strong market consensus. By contrast, the 2025 cuts are preemptive, occurring before inflation has fully met target, amid significant internal division and tariff-policy uncertainty.

This difference implies that the 2025 easing cycle may deliver less stable results. After rate cuts in 1982, U.S. GDP surged 7.2%, whereas in 2025, growth may be constrained by structural labor shortages and escalating trade frictions.

Another key takeaway is the Fed’s evolving policy framework.

In 1982, the Fed shifted from quantity-based controls to explicit interest rate targeting and began publishing rate goals, improving transparency. In 2025, the Fed is moving from an average inflation targeting regime back to a flexible inflation target, underscoring its renewed focus on policy discretion. Both adjustments demonstrate institutional adaptability to complex conditions, but the 2025 shift is more contentious because it comes before inflation has reached target, raising questions about whether the Fed is compromising its inflation mandate.

Going forward, three major challenges loom:

calibrating policy amid a “peculiar balance” of slowing labor supply and demand to avoid both overstimulation and insufficient support;

assessing the long-term impact of tariffs and distinguishing one-time shocks from persistent inflation pressures;

maintaining policy independence under political pressure to safeguard the Fed’s credibility.

Final Thoughts

The Jackson Hole Symposium, long seen as a bellwether for monetary policy, has once again provided forward guidance to markets. The policy pivot following the 1982 conference successfully curbed inflation and ushered in a period of sustained economic growth; the 2025 meeting, by contrast, seeks to strike a balance between labor market weakness and lingering inflation pressures.

The future path of monetary policy will hinge on incoming data, particularly labor market trends and inflation dynamics. The Federal Reserve may need to carefully calibrate its pace of action to avoid excessive easing that could reignite inflation, or overtightening that could deepen economic slowdown. History suggests that policy transitions must be gradual and adjusted in real time based on economic feedback.

Disclaimer: The content of this article does not constitute a recommendation or investment advice for any financial products.

Email Subscription

Subscribe to our email service to receive the latest updates