Determining the direction of yields between reflation and convergence

03:34 August 22, 2025 EDT

Key Points:

The long-term trend in US real GDP growth has clearly weakened, while the federal fiscal deficit and debt ratio continue to climb, creating a dilemma of "high debt and low growth." Revenue from tariffs will hardly change this upward debt ratio dilemma.

When nominal interest rates exceed nominal growth rates, the fiscal adjustment required to stabilize debt rises sharply. If fiscal spending is biased toward transfer payments and interest payments, the investment multiplier becomes low or even negative, further crowding out private investment and weakening productivity.

To achieve debt sustainability, we must simultaneously advance: 1) increasing potential growth (infrastructure, human capital, and regulatory reform); 2) managing financing costs (stabilizing the issuance curve and reducing risk premiums); and 3) optimizing the deficit structure (expanding the tax base, restructuring spending, and strengthening automatic stabilizers).

Revisiting the PIMCO 25+ Year Zero Coupon U.S. Treasury Bond ETF (ZROZ) raises a crucial question: Is it worth locking in a 30-year bond yield of around 4.2% amidst rising deficits, high supply, and a return to term premiums? The allure and cost of zero-coupon, long-term bonds are maximized—every small change in yield is amplified into a significant step in net asset value. The past few years have been a textbook example of this amplification effect: in the cascading cycle of "zero interest rates—repricing inflation—rising term premiums," the longest maturities have been the first to come under pressure, and even "total return" measures have suffered prolonged negative drifts. This makes the adage of "timing your bond purchases" particularly stark.

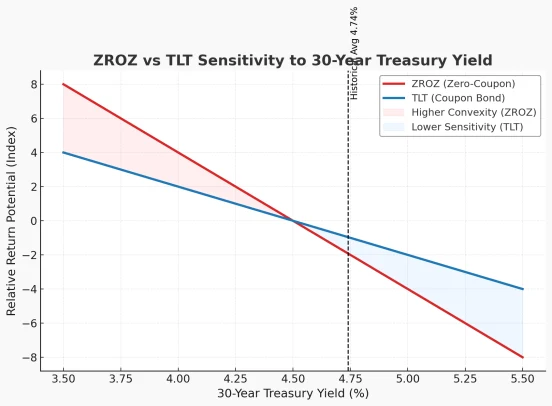

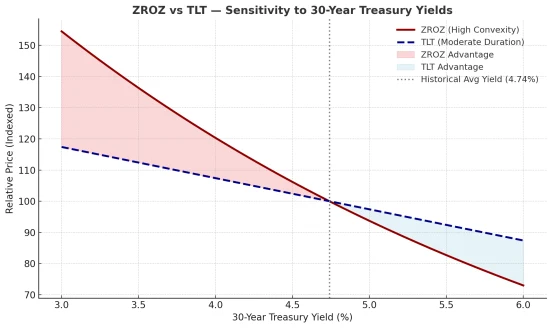

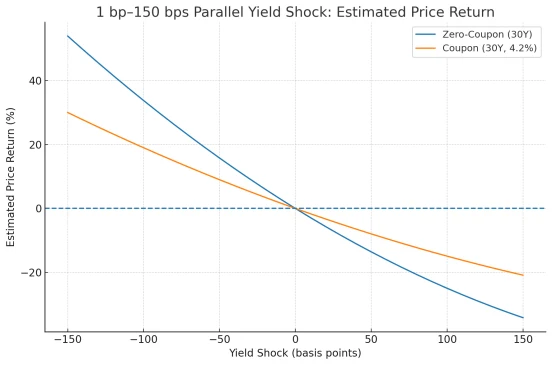

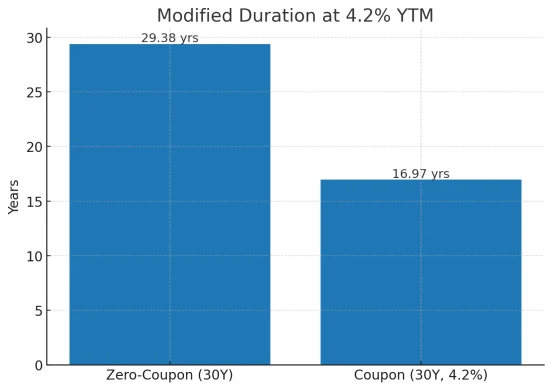

To gain a deeper understanding, we must first separate duration from "institutional variables." Zero-coupon bonds like ZROZ possess extremely high effective duration and convexity, meaning they are more resilient than coupon-bearing bonds of the same maturity if interest rates fall. However, during periods of rising interest rates or widening term premiums, drawdowns are also steeper. Long-term pricing isn't solely influenced by nominal growth and inflation anchoring; fiscal supply, central bank balance sheet contraction, marginal demand from commercial banks and the external official sector, and the shaping of duration preferences by regulatory and accounting frameworks all contribute to reassessing the "reasonable term premium." When deficits and refinancing demands shift the supply curve to the right and the price elasticity of the demand curve decreases, the yield center naturally rises, amplifying the negative sensitivity of zero-coupon bonds.

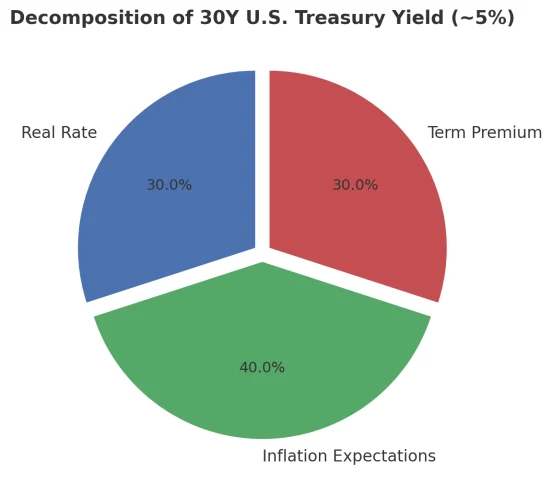

This doesn't mean that ultra-long-term bonds have lost their strategic importance. On the contrary, once the credibility of the inflation decline increases, growth enters a slow steady state, and policy uncertainty converges, long-term prices often experience a "data-ahead" price correction. If the 30-year nominal interest rate is broken down into "long-term equilibrium real interest rate + inflation expectations + term premium," as long as confidence in the inflation anchor is sufficient to suppress the second component and credible commitments to the fiscal path stabilize the third, the current nominal interest rate range has the potential for downward convergence. For ZROZ, this convergence is not linear, but rather nonlinear with a convexity bonus—the faster the interest rate declines, the more likely it is to recover previously accumulated "paper losses" at a higher slope.

Therefore, the question of whether to lock in duration around 4.2% ultimately depends on how you price three factors: the resilience of the inflation anchor, the credibility of the fiscal rule, and the cyclical position of the term premium. If your fundamental assumption is that "inflation returns to and stays within the target range, the fiscal trajectory has a verifiable consolidation framework, and the term premium is already at a high quantile," then making the longest duration the core of your portfolio is not only feasible but may even outperform the mid-term duration after risk adjustment. However, if you believe that "the upward shift in the inflation center has not yet concluded, supply pressures are still rising, and policy volatility is increasing term risk compensation," then the same 4-digit term is not cheap. ZROZ is more like a short option position sensitive to macro reflation and fiscal deleveraging.

At the tactical level, a pure "all-or-nothing" approach isn't necessary. Treating duration as a "budget" rather than a "view" is more appropriate for the current noisy environment: using the medium- to long-term (10-20 years) as a base, with a small amount of ultra-long zero-coupon assets to shoulder the "convexity burden," and using inflation-protected bonds (TIPS) or interest rate swaps to hedge some of the inflation and term risks, is a more robust configuration. Simple, enforceable discipline can also be employed to prevent subjective drift: only increase zero-coupon holdings when the 30-year yield is in the upper quantile of a set target, and reduce to the benchmark weight when it falls back to the median range. Meanwhile, the portfolio's DV01 is maintained within a tolerable threshold to avoid being "driven by" a single auction or piece of data. For investors unable or unwilling to engage in instrumental management, it's also practical to view ZROZ as a "cycle starter waiting to be realized"—its win rate and profit-loss ratio are highly dependent on the downward trend in interest rates, rather than the repeated fluctuations within the range.

Let's return to the original question: In a phase of rising supply and unresolved deficits, should we "leverage and lock duration all at once" around 4.2%? The answer shouldn't be a generalized yes or no, but rather defined by conditions and a cadence. Once you see proxy indicators of term premiums decline, more verifiable signals of a fiscal path, and easing high-frequency signs of inflationary stickiness, ZROZ's risk-reward ratio will rapidly improve. Until then, recognizing path dependence and using layered duration and segmented position building to smooth out "wrong timing" often helps protect the net asset value curve better than betting on a single point. To sum it up: The longest duration is never an asset that is "always right"; it simply amplifies the direction of the macro anchor into a price gradient. When the anchor is on your side, ZROZ's value is extraordinary; when the anchor is on the other side, the cost is also magnified.

Pushing duration to the limit and putting interest rate views under the magnifying glass

PIMCO is renowned for its fixed income offerings, and its family of closed-end funds is highly regarded. However, the passive index ETF ZROZ embodies the purest approach to "extreme duration." Its market capitalization has approached $1.5 billion, with active secondary market trading and relatively manageable entry and exit costs. The underlying index is the ICE BofA US Treasury Long Principal STRIPS, which has a nearly 30-year history, a transparent tracking framework, and a management fee that is typically low for passive bond funds. Established in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, this fund focuses on holding "principal STRIPS" (zero-coupon bonds that separate the coupons from the principal and retain only the principal) of US Treasury bonds with a remaining maturity of approximately 25 years or more. Its zero-coupon structure, with purchases at a significant discount and a lump-sum payment upon maturity, pushes interest rate sensitivity to the upper limit of the portfolio.

To understand the first principles of ZROZ, we must first acknowledge two things. First, ultra-long zero-coupon bonds = ultra-high duration + high convexity. Without the "cushion" of coupons, the net asset value is extremely sensitive to every basis point change in yield. However, once interest rates decline, convexity amplifies price elasticity. This is why ZROZ often outperforms conventional long-term bond ETFs in markets where expectations of rate cuts precede and term premiums decline. Second, ZROZ drawdowns often resonate with the macroeconomic dynamics of "reflation + increased fiscal supply + rising term premiums." Deficit financing lengthens issuance duration, central bank balance sheet reduction suppresses marginal buying, and the decline in duration preference among officials and banks all drive up long-term risk compensation. During such repricing phases, the negative elasticity of zero-coupon bonds can make losses appear disproportionate.

This also explains why the question of whether "zero-coupon long-term bonds are good" isn't a static question, but rather a bet on a macroeconomic anchor. Breaking down the 30-year nominal interest rate into three components—long-term real interest rates, inflation expectations, and term premiums—if you believe the inflation anchor has returned to the target range and stabilized, the fiscal path has become more verifiable, and the term premium is at a high quantile with room to fall, the risk-reward ratio of ZROZ (Zero-Rate Bond) transforms from a "high-volatility bet" to a "convexity-rich convergence trade." Conversely, if you're concerned about a stickier inflation core and the risk premium driven by Treasury supply and policy uncertainty, then the same long-term interest rate of just over 4% isn't cheap, and the left-side risk of ZROZ remains real.

At the asset allocation level, the value of ZROZ isn't limited to betting on rate cuts. It's often used as a tail hedge against equities: when the economy unexpectedly weakens, nominal growth declines, and the long-term market experiences a sharp decline, the price gradient of zero-coupon bonds can provide a small, still-strong "reverse growth." Of course, this hedge will fail in a scenario characterized by an inflation shock and rising nominal interest rates, and may even amplify portfolio volatility. Therefore, a more sensible approach is to use ZROZ as a "convex duration position," combining it with mid-duration Treasury bonds, TIPS, and even cash to form a "layered duration" framework: mid-duration bonds provide steady-state exposure, a small amount of ZROZ captures the nonlinearity of rapidly declining interest rates, and TIPS mitigate the directional bias of inflation surprises. In practice, duration can be treated as a "budget" rather than a "viewpoint." For example, a zero-coupon bond's weighting can be gradually increased only when the 30-year yield reaches a historically high quantile, and reduced to a benchmark weighting when it falls near the median. This approach maintains the portfolio's DV01 within its tolerance range to avoid being "distorted" by a single auction or data point.

Several often-overlooked details are also important to note. First, tracking error stems from more than just fees and sampling. The liquidity and valuation spreads of STRIPS relative to "on-the-run" bonds can widen during periods of stress, potentially leading to short-term price performance diverging from that of conventional long-term bond ETFs. Second, zero-coupon bonds are taxed on an accrual basis in the US under the original issue discount (OID) structure, potentially generating taxable income even without cash coupon payments. ETF structures typically pass on funds through distributions or reinvestments, so investors should assess liquidity and tax implications based on their tax jurisdiction and account type. (This does not constitute tax advice.) Third, ZROZ's "roll-down" yield path differs from that of coupon-bearing bonds. Without the natural rebalancing mechanism provided by coupon reinvestment, its net asset value path is driven more purely by the shape and position of the interest rate curve.

Laying all this out, the conclusion in the title becomes clear: ZROZ isn't a "forever right" long-term bond artifact, but rather a price-slope amplifier that translates your judgment of the inflation anchor, fiscal rules, and term premium. When the macro anchor is on your side, it provides highly efficient duration exposure; when the anchor is on the other side, it penalizes positions with equal force. A more realistic approach isn't to pin success or failure on a single point, but to use disciplined position building and layered duration to smooth out timing errors. In the latter half of the interest rate repricing, ZROZ's nonlinearity may be precisely the most scarce component of a portfolio, and the one that needs to be used with restraint.

Why is ZROZ painful and when is it useful?

According to the first principles of bond pricing, the duration of a zero-coupon bond is equal to the maturity itself. Because it has no interim cash flows, its sensitivity to small yield fluctuations is maximized. Of two long-term bonds from the same issuer, with the same maturity and yield to maturity, the zero-coupon bond's price is inevitably more elastic to interest rates. The coupon on the interest-bearing bond is "reinvested" along the way, effectively "distributing" some of the duration over time, thereby weakening the single-point impact of the net asset value on the interest rate. Therefore, a zero-coupon bond isn't simply "high duration" but "enhanced duration": it directly translates your judgment of the ultimate interest rate outcome into a larger slope in the net asset value.

ZROZ's volatility stems precisely from this design. It tracks the STRIPS index of long-term US Treasury bonds, a portfolio with extremely long duration and strong convexity. Over the past five years, this structure has borne a heavy price amidst historically rare interest rate repricing: nominal and real interest rates have regressed from near zero/negative to more "normal" ranges. Fiscal supply increases and quantitative tightening have combined to push up term premiums, while the stickiness of inflation shocks has prolonged the high interest rate period. Even without any credit risk, this "pure interest rate risk" alone is sufficient to generate significantly negative returns. In other words, ZROZ's pain isn't a product issue, but rather a drastic shift in the underlying macroeconomic landscape: when long-term interest rates repriced from 0.5% to 5%, long-duration, zero-coupon portfolios were the first to be hit. This is a vivid manifestation of duration theory in action.

But if you extend the timeframe and apply the logic, you'll see another side. Zero-coupon, long-term bonds also possess higher convexity—when yields decline, the positive nonlinearity of their prices is amplified, often outperforming coupon-bearing bonds of the same maturity. Furthermore, in an environment of unexpectedly weaker growth and a stable inflation anchor, long-term interest rates typically fall faster than short- and medium-term ones. This "pure duration" asset, ZROZ, possesses exceptionally high beta elasticity. Its value is never about "always buying," but rather "under what set of assumptions is it worth buying, and how much to buy?" If your medium-term baseline is: inflation returns near target and stabilizes, the fiscal path and supply curve are relatively predictable, and the term premium is at a high quantile with room to fall, then ZROZ provides highly effective interest rate convergence exposure. Conversely, if you're concerned about a stickier inflation core, prolonged high deficits and supply, or increased risk compensation due to policy uncertainty, then the same coupon rate isn't "cheap," and the left-tail risk of zero-coupon bonds is greater.

Putting ZROZ back into asset allocation rather than "single-product speculation" offers at least three key uses worth considering. First, as a tail hedge for equities. During periods of sudden economic decline or financial contraction, long-term interest rates tend to decline rapidly, and the nonlinear nature of zero-coupon stocks can amplify this protection. However, in years dominated by inflation shocks and when the correlation between stocks and bonds turns positive, this type of hedge will fail. Therefore, a more prudent approach is to use a layered duration framework: medium- and long-term government bonds provide steady-state exposure, a small proportion of ZROZ captures the convexity of the tail decline, and TIPS hedge against inflation surprises. Second, as a "view concentrator." When you judge that market-priced forward rates and term premiums significantly overestimate the duration of high interest rates, ZROZ can amplify alpha more than conventional long-term bonds, but this presupposes disciplined management of positions and DV01, avoiding letting a single data point or auction determine the fate of the portfolio. Third, as a "rules-driven" tactical position. Duration is not black and white. Simple entry/exit disciplines can be set: gradually increase allocations only when the 30-year real interest rate or ACM term premium is at a historically high percentile; when it falls back to near the median, it is reduced to the benchmark; each adjustment controls the incremental DV01, and does not bet on the calendar, but only on the percentile.

Details are equally important. During periods of stress, STRIPS may offer lower liquidity and valuation spreads than current bonds, leading to differences in short-term tracking compared to conventional long-term bond ETFs. Zero-coupon bonds are often taxed under OID rules under the US tax system. While they have no coupon cash flows, they may have taxable "interest." Therefore, multi-jurisdictional investors should assess their true returns based on their account type and tax arrangements. The rollover path for returns differs from that of interest-bearing bonds, lacking the natural buffer of "coupon reinvestment." Net asset value is driven more purely by the shape and position of the yield curve—a combination of advantages (pure perspective) and risks (greater vulnerability).

Putting all this together, a more balanced conclusion emerges: ZROZ is a tool that maximizes duration and magnifies interest rate views. It can contribute to portfolio resilience more efficiently during periods of falling interest rates and declining term premiums; however, it can equally amplify losses during periods of reflation and rising supply. Rather than asking, "Is now a permanently good time?", it's better to first answer three more fundamental questions: What is your medium-term outlook on the inflation anchor and nominal growth rate? Do you believe the term premium will mean revert or shift upward? What DV01 can your portfolio withstand, and how long can it take for a drawdown to recover? Only with these answers is ZROZ a suitable tool; otherwise, it simply reflects uncertainty multiplied back onto the net asset value.

ZROZ's "starting yield" and the dilemma of long-term bonds

Since the last tracking, the repricing of long-term interest rates has pushed the portfolio's yield to maturity above approximately 5%. For an ETF with long-term zero-coupon US Treasury bonds as its underlying asset, this "starting yield" is the primary criterion for assessing the rationality of the allocation: in a world without credit risk and with the hold-to-maturity assumption valid, the annualized return of long-term holdings is largely anchored by the starting yield. It's important to note that although zero-coupon bonds don't pay coupons, the fund still "earns" interest under tax law (OID/original issue discount) and distributes it. This means that even periods without cash flow on the books can generate taxable income—a factor that directly impacts investors' actual holding experience.

The difficulty lies in supply and term premiums. High fiscal deficits and continued net supply of government bonds in peacetime, coupled with the tail effect of central bank balance sheet reduction or reduction, will all increase market demands for "term compensation." Tariffs were once seen as a source of "paying the bill" for the deficit, but their macroeconomic side effects (disruptions to prices and growth) and policy uncertainty often exert opposing pressure on long-term interest rates after a few quarters. A more realistic framework recognizes that as long as there are no credible medium-term constraints on the fiscal trajectory, the central value of the term premium will remain, and a sustained, trending decline in long-term yields is unlikely. History also reminds us that rate cuts do not guarantee a decline in the long term. In an environment with a weak inflation anchor and high supply, monetary easing may even be accompanied by a "bear steepening" (a decline in the short term while the long term remains stable or rises). A return to high curve spreads is not inconceivable, and this is precisely the scenario in which ZROZ is most vulnerable.

From a pricing perspective, ZROZ pushes duration and convexity to extremes: when interest rates fall, it amplifies gains with greater nonlinearity; when interest rates rise, it amplifies losses with equal force. This leads to a symmetrical conclusion: ZROZ's bull market resilience is remarkable, but its vulnerability to bear market steepness is equally significant. Without a rapid decline in inflation to stay near target, a credible fiscal path, and a substantial compression of the term premium, a modest pullback in the policy rate alone will not be enough to support this "pure duration" asset. Instead, what truly generates a substantial beta for ZROZ is a recessionary/deflationary shock similar to those in 2001, 2008, or 2020: a simultaneous decline in both nominal and real long-term yields and a decline in term premiums. Only then does a 5% starting yield become a "compoundable excess return."

This doesn't mean ZROZ is only suitable for use in disasters. There are two more refined approaches: First, use it as a "concentrator" of ideas, tactically increasing allocations only when 30-year nominal or real interest rates are at historically high percentiles and term premiums are elevated. Downweighting when they return to the median, using percentiles rather than calendars as a discipline. Second, at the asset allocation level, employ a "duration stratification + hedging" approach to mitigate the damage from a bad scenario—using 5-10 year medium-duration bonds as a stable foundation, a small overlay of ZROZ to capture downside convexity, and using TIPS or inflation swaps to cover any tail-end of inflation. Regardless of which approach is chosen, the key issue isn't whether to buy or not, but rather the rules for "total DV01 cap, the size of a single increase, and the specific percentiles at which term premiums and real interest rates should be actively reduced."

Finally, let's return to the often-overlooked key point: long-term pricing is ultimately a race between "r and g." If nominal growth (actual growth under a stable inflation anchor plus moderate inflation) is not significantly lower than financing costs, the debt ratio can stabilize, and the term premium has room to fall. Conversely, even if the policy rate falls and the starting yield appears "high," fiscal and supply uncertainties will erode the long-term safety margin. For ZROZ, a 5% starting yield is a threshold, not a talisman; the true safety margin comes from ensuring that the inflation anchor, fiscal path, and term premium repricing are aligned, and whether your positioning and discipline have adequately buffered against uncertainty.

Disclaimer: The content of this article does not constitute a recommendation or investment advice for any financial products.

Email Subscription

Subscribe to our email service to receive the latest updates