How can the United States break the dilemma of "high debt and low growth"?

14:58 August 22, 2025 EDT

Key Points:

The long-term trend in US real GDP growth has clearly weakened, while the federal fiscal deficit and debt ratio continue to climb, creating a dilemma of "high debt and low growth." Revenue from tariffs will hardly change this upward debt ratio dilemma.

When nominal interest rates exceed nominal growth rates, the fiscal adjustment required to stabilize debt rises sharply. If fiscal spending is biased toward transfer payments and interest payments, the investment multiplier becomes low or even negative, further crowding out private investment and weakening productivity.

To achieve debt sustainability, we must simultaneously advance: 1) increasing potential growth (infrastructure, human capital, and regulatory reform); 2) managing financing costs (stabilizing the issuance curve and reducing risk premiums); and 3) optimizing the deficit structure (expanding the tax base, restructuring spending, and strengthening automatic stabilizers).

A year ago, TMC Research predicted that Washington's policy space would be significantly compressed amidst slowing economic growth and a failing, if not expanding, federal fiscal deficit. Twelve months later, this risk has not abated.

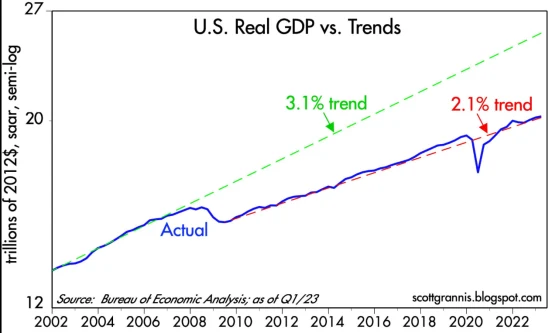

The latest data shows that nominal output, as measured by the U.S. Treasury, has exceeded $37 trillion, and the federal budget deficit widened by approximately 19% year-on-year in July. This trend is compounded by the continued decline in the U.S. economy's long-term growth. While the causes are diverse, rising government debt has clearly exacerbated the pressure. Overall, the latest data reaffirms a moderate but persistent decline in real GDP growth, adjusted for inflation.

From the interpretation of the graph, the "linear trend based on 10-year changes" represented by the blue line has clearly turned into a slow and continuous decline, indicating that the long-term gravity of the US real economic growth rate is weakening. This is a clear signal left after the current cycle and previous cycles are superimposed.

Source: scottgranis.blogspot.com

The reasons for this trend are both development-oriented and policy-driven. Mature economies naturally face the challenge of diminishing returns to scale, making it difficult to sustain high potential growth rates over the long term. This is a common problem faced by developed countries. The United States still retains advantages such as labor market flexibility, technological innovation, and deep capital markets. However, these advantages can only be steadily translated into sustained improvements in total factor productivity under effective institutional arrangements and smooth resource allocation. This is coupled with the crisis posed by persistent and substantial fiscal deficits: when the political process lacks the will or tools to stabilize debt reduction over the medium term, the drag on growth from fiscal policy will become increasingly apparent in the coming years.

The constraints on fiscal and growth can be described using the "r-g framework": when nominal interest rates exceed nominal growth rates, the primary surplus required to maintain a stable debt ratio rises rapidly. Conversely, if nominal growth rates are at least as high as the nominal interest rate, even with small deficits, the debt ratio is more likely to remain stable. Therefore, boosting potential growth, lowering effective financing costs, and improving primary finance, all within the same roadmap, are far superior to focusing on one end of the spectrum. Furthermore, the "structure" of the deficit is more critical than its "size." If new spending primarily goes to transfer payments and interest, the multiplier will be low or even negative, easily crowding out private sector investment. However, investing in high-return public capital and human capital has the potential to boost productivity, expand the tax base, and become self-financing over time. The same deficit can have vastly different goals and consequences.

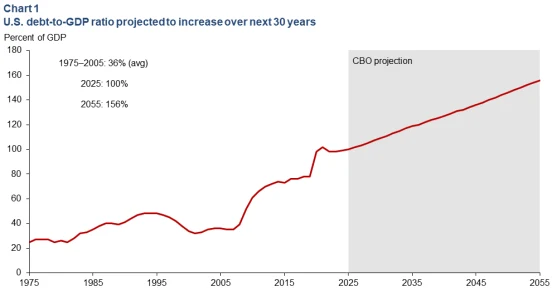

There's a buffer in the short term. The Bipartisan Policy Center's tracking shows that tariff revenue has increased significantly year-on-year since the beginning of the year, providing a temporary boost to fiscal spending. However, tariffs are essentially taxes on imports, which are typically passed on to business costs and household consumption through higher import prices, discouraging trade and investment, and weakening medium-term growth momentum. This side effect, combined with the interest burden of high debt, means that the static benefits of "trading tariffs for revenue" are likely to be offset by weakening growth momentum and rigid financing costs. Recent data indicates that the ratio of federal public debt to GDP is operating at a high level, and based on public forecasts, it is likely to continue rising until mid-century. Given this starting point, a temporary boost in revenue alone will be unlikely to reverse the upward trend.

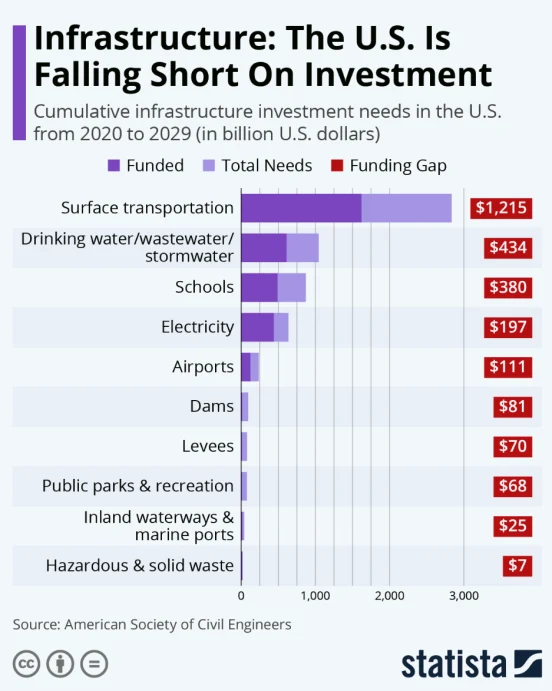

To support growth, both the quantity and quality of labor and capital are crucial. The reality of an aging population and limited marginal improvement in labor force participation rates makes net immigration and skills transfer policies crucial variables for both increasing quantity and improving quality. Regarding capital formation, manufacturing reinvestment, energy, and digital infrastructure—particularly power grids, data centers, semiconductors, and AI computing infrastructure—face long licensing cycles and strong factor supply constraints. Without simultaneous deregulation on both the regulatory and supply sides, the expansion of private investment will be difficult to sustain. Trade and industrial policies should also avoid a benefit-cost mismatch: tariffs generate static fiscal revenue but suppress dynamic corporate investment through uncertainty and rising costs. During this period of global value chain restructuring, a more cost-effective approach is to attract capital localization through regulatory certainty, institutional openness, and supply-side reforms, rather than relying on tax shifting to maintain short-term financial performance.

The effectiveness of policy design depends on whether we can shift from annual speculation to a medium-term framework. International experience shows that a combination of "spending rules, a structural reform list, and automatic stabilizer protections" is more effective in anchoring the debt trajectory without compromising cyclical stability: on the spending side, nominal or real spending growth is constrained by a rule that does not exceed potential growth; on the reform side, it focuses on high-return public investment, licensing and regulatory optimization, and expanding and simplifying the tax base, allowing resources to flow to more productive sectors; and automatic stabilizers automatically activate during recessions, mitigating the secondary damage caused by "policy reflexivity." When assessing paths, scenario-based thinking is superior to single-path assumptions: in the baseline scenario, potential growth slowly declines, interest rates fall only slightly from high levels, and the debt ratio is likely to remain elevated. In the productivity-adjusted scenario, if AI and infrastructure investment increase TFP by 0.3-0.5 percentage points, the r-g gap narrows and the debt trajectory significantly improves. In the scenario of policy stagnation and rising tariffs, the risk of a mismatch between growth and inflation, pressure on real income, and rigidly rising nominal interest rates increases the risk of a deteriorating fiscal position. The resulting policy implication is to conduct robustness tests and cross-cycle comparisons under three scenarios to avoid misjudging short-term tailwinds as reversals.

Source: statista.com

In summary, the existing data and trends point to a common core: short-term fluctuations cannot mask the downward pressure on long-term growth, and the "maintenance" bias in fiscal structures is eroding future growth. The most reliable path to halting the long-term trend (represented by the blue line) and stabilizing it, or even modestly increasing it, is not through simple tightening or stimulus, but rather through the simultaneous advancement of three key priorities within a common medium-term framework: boosting potential growth through high-return public and human capital investment, licensing and regulatory reforms, and rule certainty; reducing risk premiums and financing costs through credible fiscal rules and financial stability arrangements; and optimizing the deficit structure to direct limited resources toward higher multipliers and expanded tax bases. Only by simultaneously addressing these three key areas—increasing g, managing r, and reshaping the structure—can the long-term growth momentum shift from a slow decline to a stable platform, creating genuine space for debt sustainability.

The United States in the Age of High Debt: The Negative Cycle of Interest Rates, Debt, and Growth and the "Three-Pronged Approach" Solution

The Dallas Fed's latest calculations offer a succinct yet poignant reminder: for every 1 percentage point increase in the federal debt-to-GDP ratio, long-term interest rates rise by approximately 3 basis points. If the debt ratio continues to rise on its current trajectory over the next 30 years, this mechanism alone could push long-term interest rates up by over 1.5 percentage points. Rising interest rates are not neutral—through three channels: higher capital costs, valuation discount rates, and fiscal interest payments, they depress private investment and potential growth, while increasing the government's difficulty in rolling over funds, creating a negative "interest rate-debt-growth" loop.

The crux of the matter remains the structural mismatch between revenue and expenditure: fiscal revenue growth is struggling to keep pace with expenditure rigidities, especially with the inertial rise in mandatory spending and interest burdens, limiting the feasibility of promoting consistent spending control within existing political constraints. Demand-side stimulus is also increasingly difficult to gain support from political and cyclical perspectives, and its marginal multiplier is declining in an environment of near-full employment. This is compounded by long-term constraints on population and labor supply. The Congressional Budget Office has clearly stated that without net immigration, the US population will begin to shrink in the early 2030s. This will further depress potential growth and widen the "r-g" (nominal interest rate minus nominal growth rate) gap through lower labor input and weaker innovation diffusion.

Within this macroeconomic framework, the two main transmission mechanisms of debt expansion on growth become clearer: first, through a "crowding-out effect," it weakens capital formation, thereby depressing labor productivity; second, by raising term premiums and central interest rates, it increases the proportion of government interest expenditures, further compressing the fiscal space available for high-multiplier investment. Similar headwinds are not unique to the United States; many developed economies are experiencing the triple constraint of "high debt, low growth, and interest rate repricing." Relatively speaking, the United States still benefits from deeper capital markets, a stronger technology ecosystem, and the reserve currency dividend. These factors will help maintain the relative attractiveness of financial assets in the short term, but they cannot replace the need to correct fundamental imbalances.

Source: dallasfed.org

The solution lies not in focusing on a single area, but in simultaneously advancing three fronts within the same medium-term framework:

First, boost potential growth (increasing g) . Redirect limited fiscal resources from low-multiplier transfers and low-return projects toward proven positive net present value public capital and human capital investments: power grids and energy systems, digital and data center infrastructure, transportation backbones, basic research, and skills education. For the private sector, licensing and regulatory reforms, institutional facilitation of interstate factor flows, and policy certainty for emerging productivity with high sunk costs (such as AI and semiconductors) often stabilize investment expectations more effectively than nominal subsidies.

Second, manage financing costs (lower r) . Without eroding market-based price signals, reduce term premium volatility through robust debt duration management and a predictable issuance curve; lower risk premiums through a credible medium-term fiscal path; and strengthen financial stability tools to avoid procyclical amplification of interest rate and credit spreads. Rather than relying on administrative interest rate cuts, it's better to use clearer rules and less policy uncertainty to allow the market to price its own future based on lower risk premiums.

Third, reshape the deficit structure (optimizing composition rather than focusing solely on total volume) . Fiscal consolidation should focus on "improving the structural primary surplus and rebalancing the expenditure structure": reducing procyclicality by broadening the tax base rather than simply raising marginal tax rates, eliminating inefficient tax expenditures, and introducing expenditure rules (ensuring that expenditure growth does not exceed potential growth) and automatic stabilizers. For mandatory spending, long-term parametric reforms should replace short-term, impulsive cuts to ensure a path that is politically feasible and economically sustainable.

Population and labor supply are the most realistic and sensitive components of the growth equation. Net immigration not only replenishes quantity but also improves the quality of skills. Within the bounds of social consensus, targeted immigration and training in key shortage fields (engineering, computing, nursing, vocational education) often yield the fastest marginal returns. Rather than oscillating between tariffs and industrial substitution, it is better to focus on improving the quality of factor supply and the efficiency of innovation diffusion—the latter offers a more lasting boost to potential growth.

Putting these factors back into the "r-g" framework yields an intuitive conclusion: as long as nominal growth (real growth plus inflation under a robust inflation anchor) does not significantly fall below nominal financing costs, the debt ratio is expected to stabilize. Conversely, even if deficits converge in the short term, if potential growth continues to decline and financing costs become rigid, the debt trajectory will still be biased upward. In other words, the essence of fiscal sustainability is not "spending less" or "collecting more taxes," but rather "investing more of each unit of fiscal resources in uses that increase g and lower risk premiums."

From an international perspective, the United States' relative advantages are likely to persist for the foreseeable future: its deep capital markets, rule of law and governance framework, and technological and entrepreneurial spirit ensure its continued ability to absorb global savings even in an era of high debt. However, this relative advantage is not a permanent safeguard. The longer adjustments are delayed, the greater the scale and cost of structural consolidation required—reflected in more drastic policy choices (redistribution of taxes, benefits, and investment), higher political coordination costs, and steeper growth losses.

Ultimately, the current fiscal and growth dilemma isn't a matter of "whether it can be solved," but rather "in what order, with what tools, and over what timeframe." A practical approach is to anchor expectations with medium-term rules (expenditure growth ceilings and structural primary balance targets), boost potential growth through supply-side reforms (infrastructure, human capital, and licensing reforms), reduce term and risk premiums through prudent debt management and reduced uncertainty, and underpin growth with demographic and skills policies. This combined approach of "raising GDP, stabilizing GDP, and adjusting the economy's structure" can partially offset upward pressure on long-term interest rates and potentially dismantle the negative debt-growth feedback loop. On the other hand, if the economy continues to oscillate between short-term trade-offs, allowing worsening deficits and declining potential growth to mutually reinforce each other, future adjustments will be more difficult, more drastic, and more disruptive.

Disclaimer: The content of this article does not constitute a recommendation or investment advice for any financial products.

Email Subscription

Subscribe to our email service to receive the latest updates