The truth behind the dollar's "collapse theory"

09:12 August 9, 2025 EDT

Over the past year, financial media has been filled with alarmist claims of an "imminent collapse" of the US dollar. Financial influencers on social media have brandished charts depicting the "dollar's doom," while prominent figures in financial publications have loudly warned of the risks of dollar devaluation. Such rhetoric has gained considerable momentum. Indeed, such claims easily attract attention—high inflation, excessive money supply, fiscal deficits, and so on—making it sound as if a crisis is imminent. However, while some of these concerns are warranted, many headlines seem more like sentimental speculation than fact-based analysis.

Those peddling gold, silver, or other "doomsday assets" often harp on the downward trend in the U.S. dollar index. But here's the thing: it doesn't actually mean the dollar is losing value; it simply reflects inflation, a common and widely expected part of economic growth.

Over time, prices naturally rise as population growth, rising incomes, and expanding consumption drive demand. This is particularly true in post-industrial, service-oriented economies, which inherently promote credit expansion and capital investment. What we often say is not that the dollar is depreciating, but rather that the economy is expanding.

Next, let’s explore the true relationship between the concept of “depreciation” and economic growth.

inflation

Let's first clarify two often confused concepts: inflation and currency devaluation. While both reduce the purchasing power of the dollar, their nature and causes are different.

Inflation is a general rise in prices caused by an imbalance between supply and demand. When wages rise and consumer demand surges, but the supply of goods and services fails to keep pace, prices naturally rise. This has been particularly evident during the post-pandemic economic recovery—against a backdrop of constrained supply, policy stimulus has further boosted demand, thus fueling inflation.

Currency devaluation refers to the overall weakening of the value structure of a currency, often accompanied by deliberate policy manipulation. For example, in ancient Rome, reducing the silver content of coins to expand the money supply and repay debts was a classic example of currency devaluation.

But in today's fiat currency system, money is no longer pegged to gold or silver, and its "integrity" cannot be "diluted." Even if the government "prints" large amounts of money, it cannot simply be equated with currency devaluation. While some bears use "currency devaluation" as a crisis-proof tool, attempting to incite public panic, the reality is far less fragile than they claim.

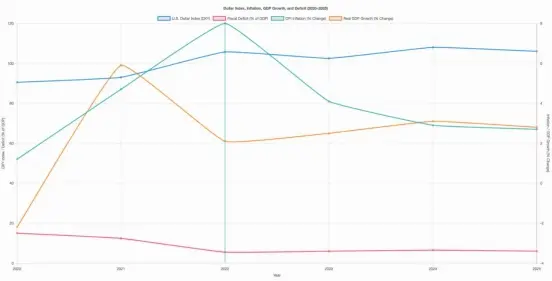

Investors need to understand that global confidence in the US dollar remains strong. Despite high fiscal deficits and rapid expansion of the M2 money supply, the US dollar has not been abandoned; instead, it remains firmly at the core of the global financial system. The US dollar still accounts for approximately 80% of global trade settlements, and nearly 60% of global foreign exchange reserves are held in US dollar assets. The US dollar index also remains strong, demonstrating its widespread acceptance.

Therefore, the so-called "dollar devaluation theory" is either prematurely pessimistic or deliberately misleading. In the current reality, the dollar has not weakened, but remains the world's most resilient reserve currency.

The role of growth

If the government expands the money supply faster than the economy actually grows, then it seems reasonable to worry about "currency debasement." In this case, the excessive money supply could trigger inflation.

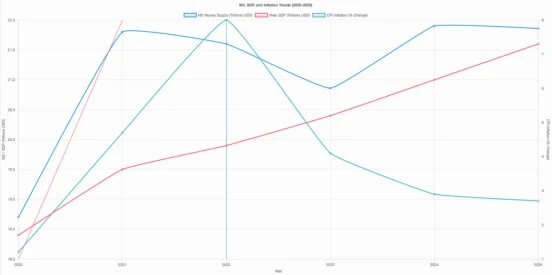

In fact, we have experienced a similar scenario—the surge in M2 during the pandemic was unprecedented. In 2020 and 2021, the US government injected over $6 trillion into the market. However, it's important to emphasize that this drastic intervention took place in a specific context: the world was facing the worst economic shock since the Great Depression. To avert an economic collapse, the Federal Reserve and fiscal authorities took unprecedented action, and these measures largely achieved their goals of stabilizing markets and avoiding systemic risks.

This rapid monetary expansion did shift the supply-demand equation, driving up prices. However, it also contributed to a rapid economic rebound, lower unemployment, and a short-term boost to overall demand. Without sufficient monetary injections, the economy might have fallen into a deeper recession.

Therein lies the problem: Many people, seeing a surge in the M2 curve, instinctively interpret it as evidence of "currency devaluation." But this is a one-sided view. The money supply must grow in tandem with the expansion of the economy; otherwise, deflation and sluggish growth will result. Looking at long-term trends, the US money supply has broadly kept pace with GDP expansion since 1959. This is a fundamental logic underlying the operation of the modern economy: credit expansion and monetary growth are the foundation for supporting economic activity.

Therefore, the key to determining whether an economy is in the grip of currency devaluation is not whether the money supply has increased, but whether this increase far exceeds the economy's actual growth potential. Otherwise, "currency devaluation" is nothing more than a misleading label that represents panic.

A more accurate way to assess whether monetary policy is excessive is to compare the ratio of M2 to GDP. Historical data shows that the two indicators have a high degree of long-term correlation. Even during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ratio of M2 to GDP never exceeded 100%, indicating that the expansion of the money supply has generally kept pace with economic output growth.

More importantly, this ratio is currently declining, not rising. This means that the monetary expansion during the pandemic did not permanently lead to systemic imbalances. Instead, as the economy recovers, the relationship between money and economic size is gradually returning to normal. In other words, claims of "currency flooding" or a "sharp devaluation of the US dollar" are untenable in the face of macroeconomic data.

Growth trend of the US dollar

Every few decades, there are predictions of the dollar's end. In the 1980s, it was Japan; in the early 2000s, it was the euro; today, it's China or cryptocurrencies. However, the reality is that these alternatives have always been unable to replace the dollar's core strengths: the world's deepest capital markets, a stable rule of law, and the global reach of the U.S. economy and military.

The US dollar remains the "cleanest dirty shirt in the global laundry basket." This doesn't mean it's without flaws, but rather that, in the absence of stronger, more credible global alternatives, the US dollar remains synonymous with trust, liquidity, and legal protection. Even gold, often considered the "ultimate currency," relies on the US dollar as the foundation for its trading and pricing.

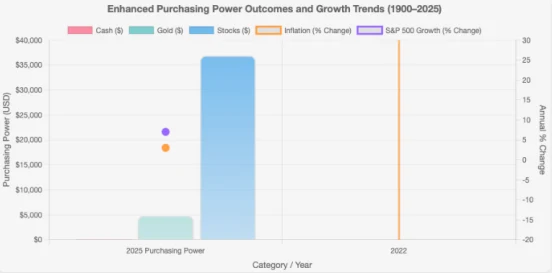

In reality, what investors should be wary of is not depreciation itself, but rather the long-term erosion of purchasing power by inflation. Therefore, the real solution isn't panic selling dollars, but ensuring that the long-term growth rate of personal assets exceeds the inflation rate—in other words, protecting against depreciation risk through investment rather than hoarding.

For example: In 1900, a high-end men's suit cost about $35; today, it's closer to $2,000. If you had tucked $41 under your mattress back then, it might only buy a few discounted polo shirts today. But if you had used that money to buy two one-ounce gold coins, you could not only buy the suits but also have about $1,600 left over—a testament to gold's inflation-fighting power. On the other hand, if you had invested in stocks, you could now buy 15 suits based solely on capital gains from long-term stock price appreciation (not including dividends). This demonstrates that the best hedge against inflation is always to own growth assets.

So why does the "dollar collapse" narrative still attract so much attention? Because fear is more appealing than hope. Negativity bias makes us more drawn to threatening topics, even if they're not entirely true. Overly exaggerated fear can confuse truth with noise.

Investors' task is to distinguish facts from complex information. While we should be concerned about inflation, deficits, and policy risks, we must also remember that the US dollar remains the cornerstone of the global financial system. This isn't because it's invulnerable, but because there are currently no viable alternatives.

So, let me emphasize again: what we should really worry about is not the "devaluation of the US dollar", but how to use your assets to defeat time and inflation.

Disclaimer: The content of this article does not constitute a recommendation or investment advice for any financial products.

Email Subscription

Subscribe to our email service to receive the latest updates